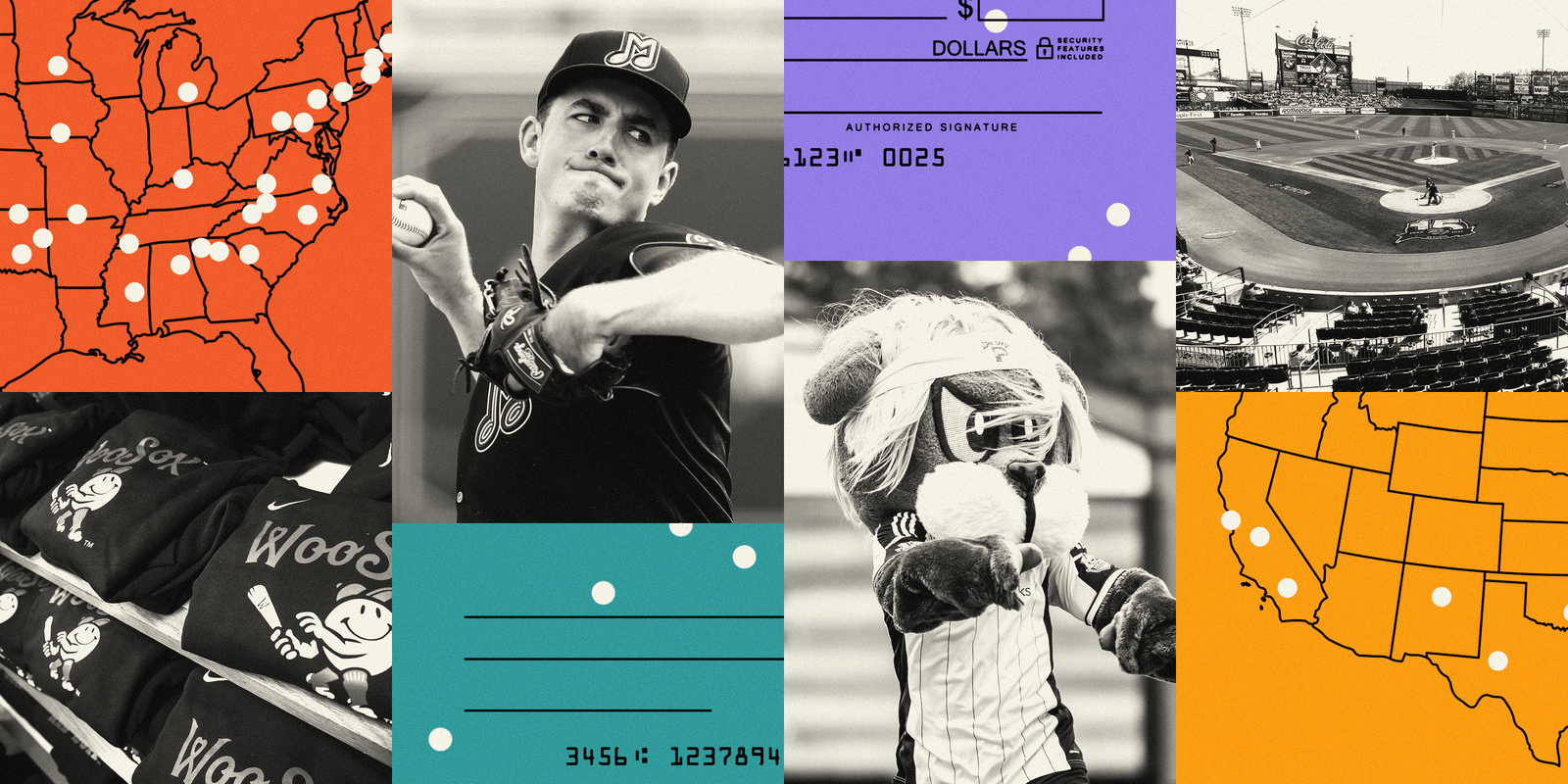

A new group is buying up minor league baseball teams at a feverish pace. What’s the end game?

[ad_1]

WAPPINGERS FALLS, N.Y. — The artificial turf at Heritage Financial Park is new. So is the right-field wall that opens wide enough for an 18-wheeler to haul concert equipment onto the field. The party deck is sponsored by a brewery that’s 10 miles away, giant windows have been installed around the corporate event space overlooking left field, and the renovated home clubhouse, where the Hudson Valley Renegades dress before games, has two indoor batting cages flanked by state-of-the-art data and motion-capture technology.

This is Class-A baseball in 2024. Quirky and local, but also big business that’s booming. Minor-league attendance is up and approaching pre-pandemic levels, new ballparks are being built, and existing franchises are selling at what are believed to be record prices. These are not the wooden bleachers and potholed infields of old.

At the center of this transformation is Diamond Baseball Holdings, a three-year-old company that owns more than a quarter of all minor league clubs. From a ground-up franchise in Spartanburg, S.C., to long-established clubs in Louisville, Ky., and Lansing, Mich., to their most recent purchase of the Harrisburg Senators in Pennsylvania, Diamond Baseball Holdings (DBH) now owns 32 of 120 affiliates, and its founders said they are still “aggressively in acquisition mode.”

“We are agnostic to geography. We are agnostic to club affiliation,” executive chairman Pat Battle said. “If you’re one of the 120, we are interested.”

The DBH portfolio has grown at a rate, and to a size, that would have been impossible five years ago. It is a byproduct of Major League Baseball’s 2020 takeover of the minor leagues, which yanked affiliated baseball out of more than 40 communities and shifted minor league control to the MLB office. Commissioner Rob Manfred’s “One Baseball” initiative seeks to put every aspect of the game under one umbrella — that of the major league team owners — from Yankee Stadium to the Little League World Series, and all things in between.

In the middle of that plan is DBH, co-founded by former college sports licensing executive Battle and longtime minor league owner Peter Freund, and financially backed by private equity investment firm Silver Lake.

“We felt like, man, if we have Major League Baseball aligned with minor league baseball really for the first time ever, this could be an unbelievably exciting time to do it,” CEO Freund said.

Beyond its ownership role, DBH has a strategic partnership with MLB to help negotiate national sponsorships and branding opportunities on behalf of all minor league franchises, and it also plays a role in consumer product licensing for all 120 teams.

Major League Baseball declined to speak on the record about DBH, and some minor league owners did as well, noting that both Freund and Battle are close with Manfred. The owners who did agree to talk about DBH said it has paid good prices for teams and seems to run them well — it’s largely retained local staff and invested in communities. Yet there are concerns about its outsized influence in a rapidly evolving industry, and whether minor league baseball — long considered a hyper-local, mom-and-pop enterprise — can thrive within a massive corporate structure.

“They think they can be a little more efficient, and maybe they can,” one former owner said. “But, again, MiLB is very local. You kind of need the people you need there to sell and all the stuff that has to be done on the ground. They can’t do that corporately.”

There is also some worry that given DBH’s size and reach it could impact MLB’s decision-making in the future, especially as some minor league owners fear that further contraction of teams and even greater MLB control could be in the works.

“On the one hand it is tremendously beneficial that DBH has a say because MLB can’t come in and push 120 teams around,” said one longtime minor league owner who, like some peers interviewed for this story, was granted anonymity so that he could speak freely. “However, the biggest fear that we have is that as we approach the next (minor-league contract) in several years, DBH has such influence, and the teams themselves are just a small part of DBH/Silver Lake’s overall involvement, that it’s conceivable MLB could hurt the minor-league teams to the benefit of other areas.”

From a suite overlooking the renovations at Heritage Financial Park, Freund and Battle insist those concerns are unfounded.

“Whether you’re a DBH team or not, we’re all in this together. And we do believe a rising tide lifts all boats. If a non-DBH team has success, it’s great for minor league baseball, and we celebrate that,” Battle said.

Locations and Major League affiliations for minor league teams owned by Diamond Baseball Holdings.

For more than two decades, Battle built the Collegiate Licensing Company with his father, Bill Battle. CLC acquired the licensing rights to more than 200 universities, conferences and bowls before, in 2007, being acquired by IMG to form IMG College. Battle served as that company’s senior corporate vice president and chief executive for three years.

College sports are big business, but their epicenters are not New York and Chicago. They’re in Ann Arbor, Mich., Boulder, Colo., and Tuscaloosa, Ala.

“I think MLB sees in us people who really understand Scranton and Des Moines,” Battle said. “They’re not the 30 major markets, but they’re real markets, and very important communities in this country.”

Battle briefly held an ownership stake in the Augusta GreenJackets and said he was “reading with interest” in 2020 as Major League Baseball took over the minor leagues and introduced a significantly different Player Development League (PDL) structure. Affiliates signed 10-year PDL contracts. Higher and often expensive facility standards were put in place. Affiliations shuffled and levels changed. Short-season leagues were eliminated. Three previously independent teams became affiliates, and 43 minor teams lost affiliation (many of them because their facilities were deemed insufficient). Minor-league operations moved out of the MiLB office in St. Petersburg, Fla., and into MLB’s headquarters in New York.

It was a radical, and hostile, takeover in the eyes of many.

While some owners felt a rug pulled out from under them, Battle saw a platform being raised. Many minor-league teams had long ago stopped being mom-and-pop operations. Now with Major League Baseball pushing to further modernize the business model and doing more to promote its prospects — among the new facility requirements was the ability to stream in high definition — Battle recognized an opportunity.

When Battle approached the league office, MLB not only offered reassurance he was reading the tea leaves correctly, the league connected him with a willing partner who had deep baseball connections.

“They saw it as a significant investment in minor league baseball,” Battle said. “It’s exactly what they were looking to do themselves, and within a week or two, I received a call from the commissioner’s office saying you need to meet Peter.”

As a longtime minor-league owner of the Memphis Redbirds, Charleston RiverDogs and Williamsport Crosscutters, Freund was an insider. He was friends with the other owners, familiar with the league office, and had been working with the commissioner’s office to enact the restructuring.

“This was (MLB’s) opportunity to really take this thing and bring it up to the next level,” Freund said.

In October 2021, Diamond Baseball Holdings was born — Battle came up with the name, a reference to a diamond in the rough — and in December 2021, backed by their Silver Lake capital, DBH announced an initial acquisition of 10 minor league teams. It added 11 more between December 2022 and June 2023, and three in the past few weeks.

Peter Freund, left, and Pat Battle started DBH in 2021 and they now own 32 minor league baseball teams. (Courtesy DBH)

“If you had asked me in 2019 if this scenario was even possible, I would have said you’re crazy,” said longtime Iowa Cubs general manager Sam Bernabe, whose franchise was among the first DBH bought. “Nobody would have that kind of interest in that.”

Under the old structure, various minor leagues existed as independent entities. Each worked with Major League Baseball, and no one was allowed to own multiple teams in a single league. MLB’s takeover eliminated that rule — because those leagues began to exist in name only — which cleared the path for DBH and its deep pockets.

MLB’s takeover coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, which wiped out the 2020 minor league season. Even the franchises that survived contraction faced lost revenue and massive uncertainty. Some owners saw DBH as a lifeline.

“They just came in and offered a lot more than we were (expecting) to get, honestly,” said a former owner who sold to DBH.

Other owners shared DBH’s optimism and refused to sell, believing they too could capitalize on this bright new future.

“We’re all making money,” said Larry Botel, who has an ownership stake in three minor league teams. “We’re all taking advantage of what MLB is offering us.”

DBH developed a reputation for buying teams at the high end of perceived value. Even if that had not been the case, it would have been difficult for DBH to swoop in and undercut vulnerable owners, as every sale has to be approved by the league office and pass inspection by an executive board made up of four Major League owners, four minor league owners and an independent ninth party. DBH does not have a seat on the board.

DBH acknowledged some skepticism around minor league baseball when it began buying teams, but Freund and Battle believe they’ve won over most owners.

“There were a lot of teams running their business like it’s 1975,” one current minor league owner said. “My hope is that (DBH’s) expertise in sales and marketing will elevate all the teams.”

DBH owns 20 teams at the Triple-A or Double-A level. It owns all four Atlanta Braves affiliates, three from the Boston Red Sox, and one or two from roughly two-thirds of all major league clubs. Two player development executives for MLB clubs with affiliates under the DBH banner described DBH as knowledgeable and easy to work with. “Very organized, very professional, asked all the right questions,” one said.

Not every minor league franchise sold in the past three years has wound up in the DBH portfolio. The Sacramento River Cats — Triple-A affiliate of the San Francisco Giants and one of minor league baseball’s most valuable franchises — sold in 2022 to the group that owns the NBA’s Sacramento Kings. The Goldklang Group, which has long-standing connections with Freund, sold two of its franchises to DBH but held onto another. Chuck Greenberg, who owns three minor league franchises, has kept those.

“There’s a lot of positive energy around MiLB right now that would have been difficult to foresee just a few years ago,” Greenberg said.

After taking over a team, the DBH playbook typically involves minimal surface-level changes (except in cases like Hudson Valley, where Heritage Financial Park needed significant renovation to meet the new facility standards). When DBH recently purchased the Winston-Salem Dash and Inland Empire 66ers, each news release stated that all existing staff would remain with the teams. That’s been the norm. DBH has never replaced a general manager upon acquisition. Two of its teams have rebranded — each one dropping the name of its major league affiliate in favor of something more local — and DBH announced plans to relocate two franchises: the Down East Wood Ducks will play out the 2024 season in Kinston, N.C., and then uproot to Spartanburg, S.C. The Mississippi Braves will move in 2025 to Columbus, Ga.

DBH said community connection is one of the first things it considers when evaluating a potential purchase, but it’s also crucial that facilities have a path to PDL compliance. Kinston’s Grainger Stadium is one of the oldest in the country, and Freund said DBH felt it would be nearly impossible to modernize that facility, so the company bought the team intending to build a new ballpark in downtown Spartanburg.

Tyson Jeffers, the incoming general manager in Spartanburg, transferred from the DBH-owned Hudson Valley franchise and has done everything from setting up a post office box to making connections with community leaders. Jeffers has more than a decade of minor league experience, and the difference with DBH, he said, is that everything moves faster.

“And a lot of that has to do with financials,” he said.

According to Freund, DBH has purchased 12 new video boards in the past year. They’ve bought in bulk everything from stadium lights to grounds crew tractors. When the Memphis Redbirds’ playing field fell into disrepair last season, DBH brought grounds crew members from its Springfield, Mo., and Des Moines, Iowa, affiliates to help fix it.

“You can standardize virtually every aspect of the business and still maintain that hyper-local (element),” Battle said.

Standardization and hyper-local should conflict, but DBH aims to standardize under the hood while keeping the surface-level idiosyncrasies that make minor league baseball unique. Diamond can slather the same nacho cheese across 30 franchises but still carve out space for Rendezvous BBQ in Memphis, Tenn., to provide the nachos at AutoZone Park. Same for Paul Cerda’s churros in San Jose and the Table Talk Pies in Worcester, Mass.

“It’s endless what you can do from an economy and a scale standpoint,” Freund said.

DBH is also working to finalize a strategic merchandising partnership with Fanatics, which DBH said will improve in-house retail service for select clubs by adding variety and improving the ability to replenish stock.

DBH does not own any of its ballparks. A vast majority of minor league teams play in community-owned stadiums and lease the venues. Many teams pay a flat fee to operate the stadium year-round. A minor league season guarantees no more than 75 home games, leaving at least 290 open dates. “The non-baseball might be our biggest opportunity to activate these ballparks,” Freund said.

The growth and reach of DBH has some people in minor league baseball pondering the amount of power one ownership group should hold in this evolving landscape. DBH came into existence not only with private equity money, but with a “strategic partnership with MLB for commercial rights.” The league has other people working on national sponsorships for minor league baseball, but DBH has a contract to do that as well (the group signed Oatly as the Official Oat Milk of Minor League Baseball). DBH also has a contract to help grow the licensing program and overall consumer products business across all 120 teams.

“From a national sponsorship and a national consumer products perspective, we definitely wear an MiLB hat,” Battle said. “And then as we conduct our business on ticketing, merchandising, locally at our venues, we’re wearing a DBH hat. We don’t see that as conflicted in any way.”

Other minor league owners expressed little concern about DBH filling national roles because, they figure, someone is going to be paid to find and maximize those opportunities, and DBH seems to be good at it. There’s little sense that national rights are going to be the primary driver of financial success, anyway.

“Maybe there’s an extra 10 to 20 percent revenue that will come out of this more nationalized, institutional type of approach,” Botel said. “But if you ignore the local, you’re gonna lose money. You’re gonna get creamed.”

DBH said it largely agrees with that notion. “Community is really critical for us,” Freund said.

But what does Major League Baseball consider critical?

The current PDL contracts expire after the 2030 season. Some minor-league owners expressed concern that, in seven years, MLB could further contract the minor leagues, removing the affiliation of another 30 teams — leaving three levels per Major League organization — and again raising the standards so that smaller operators will have a harder time meeting the requirements.

“We’re worried about getting squeezed out,” one minor league owner said.

DBH said it doesn’t expect or even want further contraction — the Williamsport Crosscutters, which Freund owns, were among the teams to lose affiliation in 2020. Contraction might also be more difficult now that minor league players are members of the powerful MLB Players Association, which will surely fight against the loss of hundreds of jobs.

There is also the question of what Silver Lake, the private equity money behind DBH, hopes to gain from all of this.

“Private equity is probably bad for everything except for the people that they’re buying things from, and I have a larger concern for baseball elsewhere,” one owner said. “But I think (Battle) is better at what he’s trying to do for minor league baseball than anybody.”

Some in baseball speculated early on that DBH/Silver Lake were gathering teams to bundle and re-sell as a package. A spokesperson for the private equity firm called DBH a “compelling opportunity” and said: “Silver Lake’s investments are commitments to long-term partnerships, and we are supportive of DBH’s continued work to nurture the evolution of minor league baseball while celebrating the unique culture and feel of each club.”

Freund and Battle said they’ve never discussed selling. “There’s just too much ahead to even think about that,” Freund said.

Any sale of the DBH portfolio would have to be approved by Major League Baseball, and few in minor league baseball think DBH is acting without a general understanding of what MLB might do.

Said one former owner who sold his franchise to DBH. “Nobody else would be doing this if they didn’t have some understanding of what Manfred wanted, or at the very least, his blessing.”

— Additional reporting by The Athletic’s C. Trent Rosecrans.

You can buy tickets to every MLB game here.

(Illustration: John Bradford / The Athletic. Photos: Nic Antaya / Getty; Rich Schultz, Zachary Roy, Rich Schultz / The Boston Globe)

[ad_2]

Source link